Wainwright's coastal erosion raises public health and infrastructure concerns

Wave-eroded bluffs and isolation are straining Wainwright's clinic and services, threatening subsistence ways and emergency care access for residents.

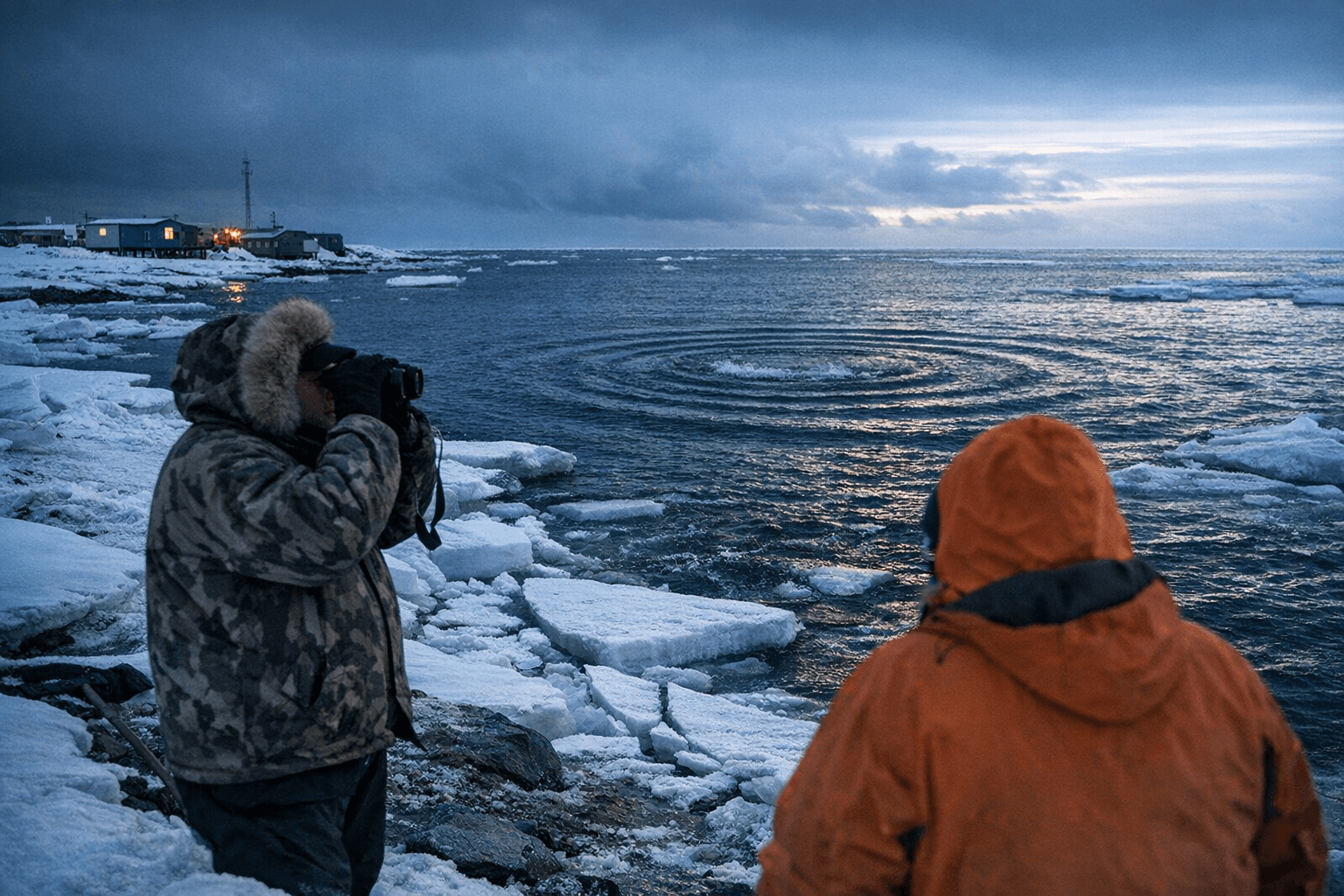

Wainwright sits on a wave-eroded coastal bluff at the tip of a narrow peninsula between Wainwright Inlet and the Chukchi Sea, placing the mostly Iñupiat community at growing risk from coastal change. That geography, combined with dependence on air and seasonal barge supply lines and a small health clinic staffed by community health aides, shapes how residents access care, food and emergency services.

Public services provided by the North Slope Borough include piped water and sewer, public electricity, trash pickup, a public safety office and a fire station, along with teacher housing and a vehicle maintenance facility. Alak School, which serves pre-K through grade 12, also offers a public swimming pool and gymnasium that double as community gathering spaces. The village corporation Olgoonik operates the Native store, and the community maintains an ordinance prohibiting sale or possession of alcohol.

Those services are essential but fragile. Limited transportation options mean serious medical cases require medevac flights to larger facilities, and freight arrives by cargo plane or barge on a seasonal schedule. For families who rely on subsistence hunting and fishing, from whaling and caribou to smelt runs, disruptions in access or timing have direct implications for nutrition and cultural life. Seasonal events such as Nalukataq and other gatherings are not only cultural keystones but also act as social health supports that help sustain community resilience.

From a public health perspective, the mix of geographic isolation, small clinical staff and infrastructure vulnerability raises several concerns. Emergency response times are constrained by weather and limited runway service. Chronic disease management and behavioral health care rest largely on community health aides who carry significant responsibility for triage, prevention and continuity of care. Housing, sewage and utility services located along an eroding bluff face long term threats that would magnify health risks if damaged.

The situation also highlights equity issues common across rural Alaska. A predominantly Indigenous community is balancing cultural survival and subsistence food security against the costs of air freight, heating fuel and maintaining facilities that were not designed for accelerating shoreline change. Policy choices at the borough, state and federal levels, funding for shore protection, durable infrastructure upgrades, expanded telehealth and support for local health workforce training, will determine whether Wainwright can sustain current services without compromising cultural lifeways.

Practical next steps for residents include continuing local planning with North Slope Borough officials, supporting community health aide capacity and maintaining subsistence practices that bolster food security. For policymakers, the priority is clear: investments that reduce evacuation need, speed emergency care and protect drinking water and sanitation systems must be paired with respect for Iñupiat traditions and self-determination.

Wainwright’s location may define many daily rhythms, from whale hunts to school events, but the choices made now about infrastructure and health services will shape whether those rhythms can endure for generations.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip