North Slope tundra fires now exceed last 3,000 years' levels

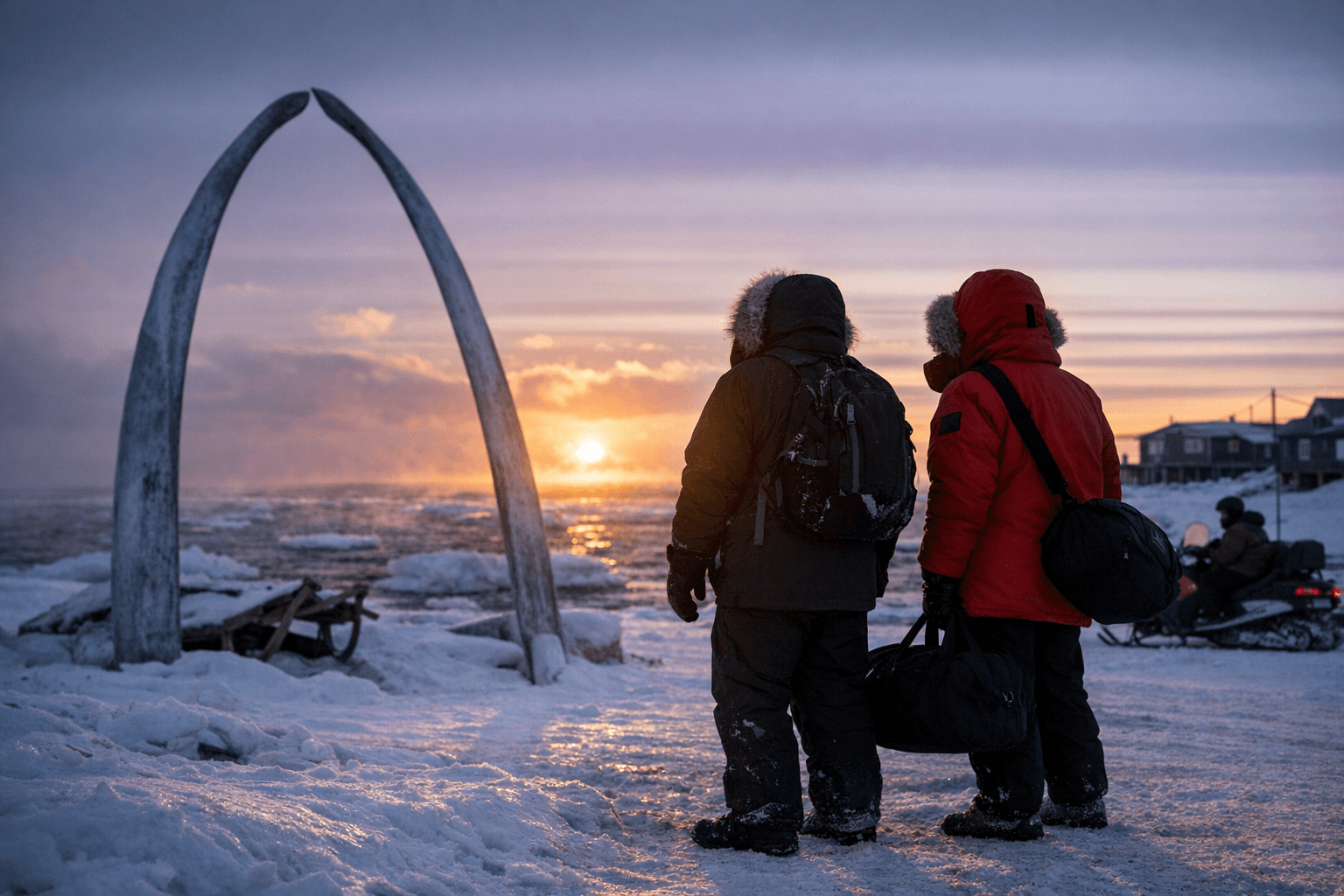

Fire activity on the North Slope surged in the 20th century, surpassing levels of the past 3,000 years. That increases risks to subsistence, infrastructure, and emergency planning.

Researchers sampling peat north of the Brooks Range found that tundra fires today are more active than at any time in roughly 3,000 years, a shift that matters directly to North Slope Borough residents. An international team including scientists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks Toolik Field Station reconstructed fire history from peat cores and satellite records, and concluded that fire frequency and intensity have climbed sharply since about 1900, with a major surge by the 1950s.

Field teams extracted roughly 0.5-meter peat cores from nine tundra sites along the Dalton Highway corridor between Toolik Lake and Franklin Bluffs. Layers of charcoal, pollen and plant remains were dated with radiocarbon and lead methods to build a continuous record stretching back to approximately 1000 B.C. That record shows low fire activity across the first two millennia, a modest uptick around A.D. 1000–1200, then another long period of low activity. Beginning around 1900, however, charcoal records and satellite observations diverged from that long-term quiet, with satellite-detected fire spikes in the late 1960s, the 1990s, and the 2000s–2010s.

The researchers link the modern rise in fire to warming-driven drying of peat soils and the expansion of woody shrubs across tundra landscapes. Shrub growth increases available fuel and flammability, and the team found signs that recent burns are hotter and consume more fuel, sometimes leaving less charcoal behind. That pattern suggests a shifting fire regime toward fewer but larger, hotter fires that penetrate deeper into peat and organic soils.

For North Slope communities, the implications are practical and immediate. Increased fire frequency and intensity threaten subsistence resources by altering habitat for caribou, birds and berry-producing plants that many residents depend on. Smoke events can compromise air quality across wide areas, complicating travel and health for elders and those with respiratory conditions. Infrastructure along the Dalton Highway corridor and energy corridors that serve the North Slope face higher risk from nearby wildfires and from thaw-related ground instability once permafrost is burned or degraded.

There are also economic and policy ripple effects. More frequent and severe tundra fires raise firefighting and emergency response costs, strain borough and state resources during longer fire seasons, and increase uncertainty for industries that depend on stable ground and transport routes. On the climate side, deeper peat combustion releases stored carbon, feeding broader feedbacks that can accelerate warming and further increase fire risk.

Local planning needs to reflect these new baselines. Better fire monitoring, updated evacuation and smoke-response plans, fuel-break strategies around critical infrastructure, and community advisories timed to longer fire seasons will all matter more than before.

The takeaway? Treat the tundra as an increasingly active fire landscape: check your household emergency plan, stay tuned to borough alerts during the spring and summer, and expect that wildland fire season is no longer a distant risk but a present one for North Slope life. Our two cents? Start conversations now with tribal, borough and state partners about strengthened fire preparedness before the next big season arrives.

Sources:

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip