Takaichi victory puts Japan’s $1.4 trillion reserves in crosshairs

Takaichi’s election win has renewed calls to tap Japan’s US$1.4 trillion FX reserves, raising market and policy concerns over intervention capacity and fiscal precedent.

Japan’s US$1.4 trillion foreign-exchange reserve stockpile is suddenly at the center of a political and market debate after Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s decisive election victory and her pledge to fast-track a two-year suspension of the 8 percent consumption tax on food. The plan, which Takaichi says she will pursue “without issuing new debt,” is estimated to create an annual revenue shortfall of about 5 trillion yen, roughly $31.99 billion by Reuters’ conversion.

Some government officials, speaking on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity, have suggested Takaichi may look to tap a recent surplus in the special government account for currency reserves. Japan posted a record surplus of 5.4 trillion yen in that account in the last fiscal year, renewing political interest in whether reserve income or principal could be repurposed for near-term fiscal needs. Takaichi noted in her campaign that Japan’s foreign reserves “were a major beneficiary of the weak yen and ‘performing very well.’”

Finance Ministry officials have been cautious in public. Finance Minister Satsuki Katayama said it “was conceivable that the large surplus could be put to use,” according to Reuters, while Business Times reported a longer Katayama comment stressing the national-security and market implications: “However, this touches on the issue of foreign exchange intervention. From the standpoint of national interest, it is not desirable to disclose all the details of what is available.”

Market and policy analysts warn that converting foreign reserves into budgetary support would cross a major institutional line. “Foreign currency reserves are, at their core, a safety mechanism to ensure currency stability,” said Saisuke Sakai, a senior economist at Mizuho Research & Technologies. “Income generated from the reserves is certainly important, but it should not be relied on excessively as a permanent funding source as it fluctuates with markets and interest rates.” Fred Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC in Hong Kong, added that “it would be risky to sell reserves primarily for fiscal purposes, and not for exchange-rate management, as this would lower available reserves for possible future intervention.”

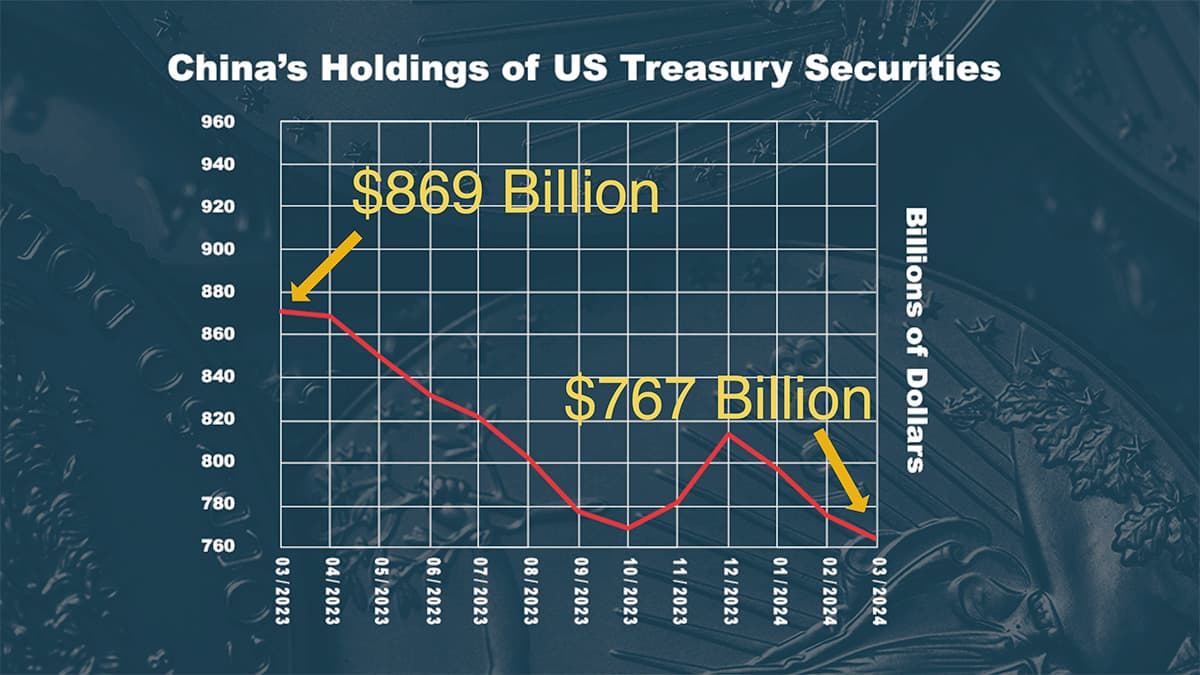

Analysts point to hard tradeoffs. Reuters described the stockpile as a “priority war-chest for future yen interventions,” noting it is “mostly held in U.S. Treasuries” and is far larger than the annual state budget. Using reserves to plug a recurring tax revenue gap would reduce Tokyo’s buffer for defending the yen and complicate coordination with the Bank of Japan, which normally acts to stabilise markets in concert with the Finance Ministry.

The debate has already “unsettled financial markets,” with investors wary that politicizing reserve use could weaken Japan’s defensive posture and elevate volatility in the yen and sovereign bond markets. Opposition parties have also seized the moment: the largest opposition group has proposed folding FX reserves together with the Bank of Japan’s ETF holdings into a sovereign-wealth fund to seek higher returns, a move that would restructure how state financial assets are managed.

Key questions remain unanswered. Officials have not specified the legal mechanism for redirecting reserve surpluses, the likely scale of any transfer, or the parliamentary timetable for deliberation. As Tokyo confronts the choice between near-term political promises and long-term currency defence, markets and policy makers will be watching whether fiscal expediency begins to alter norms that have governed Japan’s reserve management for decades.

Know something we missed? Have a correction or additional information?

Submit a Tip